Louis-Philippe ROCHON

Associate Professor, Laurentian University

Co-Editor, Review of Keynesian Economics

Follow him on Twitter @Lprochon

With data on the performance of Canada’s labour market released today, many economists and pundits on both sides of the 49th parallel are arguing that what seems to be emerging is two very clear and different paths for the US and Canadian economies. But that interpretation is not exactly correct.

Indeed, the US economy seems to be outperforming expectations, according to labour market data released last week, according to which the labour market is showing continued strong signs of life. In February alone, the US economy added more than 295,000 jobs, making it the 12th month in a row where monthly job creation is at least 200,000.That seems quite remarkable, especially since job creation is widespread across all sectors and demographics, suggesting a firmly-rooted recovery. Moreover the unemployment rate has shrunk to 5.5%, which is where it stood in May 2008. Finally, as the Secretary of Labor, Thomas E. Perez, boasted last week, February marks the first time in more than 3 decades, unemployment fell in all 50 states.

What more could you say? Apparently, the US is on course for a strong growth spurt, fuelling fear of inflation, which may convince the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates sooner than expected.

But we mustn’t believe everything the man behind the curtain is saying. As always, statistics can be used to spin any good story. A closer look reveals a somewhat different story, and in fact, a story that is much closer to our own. In the end, both the US and Canadian labour markets are much closer in character than most pundits would care to admit.

Since unemployment rates by themselves do not tell the whole story, we must dig deeper to get a fuller story.

First, there is still too much part-time employment, and the current employment ratio (the ratio of employed individual to the overall labour population) is still low, at 59.3%, a full 3 points below where it stood before the recession (labour participation rate sits at a low of 62.8%). This means that there is still an important number of workers who still desire full time jobs but just can’t get them, and left the labour market discouraged.

As American economist Thomas Palley wrote recently (see here), close to 22 million American workers are still looking to work more. Clear evidence, he says, that the US is still far away from full employment. In fact, Bucknell University professor Matias Vernengo, argues (see here) that if participation rates were at the same level today than at the end of the Clinton boom years (67%), unemployment rate today in the US would be close to 12% and not 5.5% Now that’s a difference story indeed.

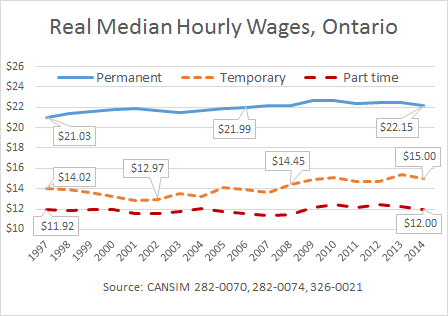

And then there is wage growth, which remains relatively weak. In fact, wage increases have averaged 0.01%, well below January’s 0.5% gain. So wage gains may in fact be slowing down. More importantly, February’s paltry wage gain is still way below productivity gains, which means there is no threat of inflation any time soon or on the horizon.

This brings us to economic policy. It is now widely expected that the US Federal Reserve will begin raising interest rates, and possibly as soon as June if not earlier. But would this increase be justified.

Given the relatively weak labour market still, and the lack of any inflationary pressure (some pundits see the inflation threat everywhere), a rate hike now would seem to be premature.

All this brings us back to Canada.

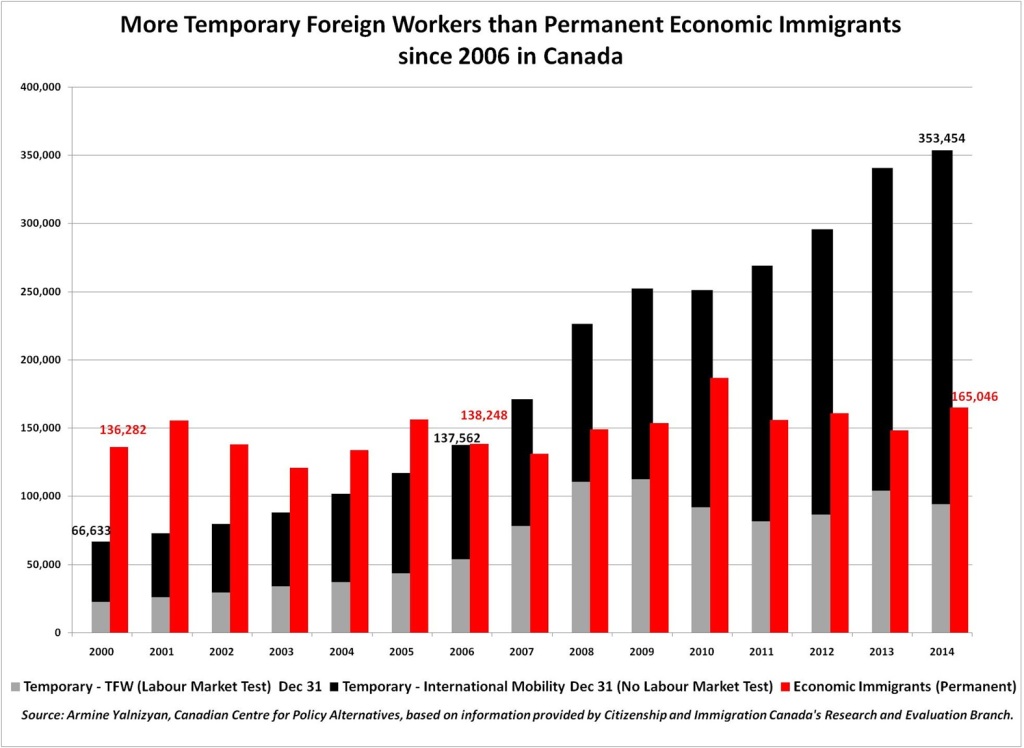

Recall that in January, while labour markets created more than 35,000 jobs (although I expect those numbers to be revised downward), these were all part-time and self-employment, thereby emphasizing the rather precarious nature of Canadian labour market. This followed a December where the economy actually shed jobs.

The latest job numbers for February are far from encouraging. In February, the Canadian economy again shed jobs, albeit less (1,000), but the unemployment rate increased back up to 6.8% from 6.6%. As I said before, we are heading in the wrong direction.

But there is more. I calculated the real rate of unemployment. If the labour force participation in Canada were at the same level as at the beginning of the crisis, then Canada’s real unemployment rate would be closer to 9% today.

This is as far away from full employment as we can get.

It is becoming overwhelmingly clear that both economies are suffering considerably, and both economies are still far from a sustained recovery, although Canada’s economy is doing far worse.

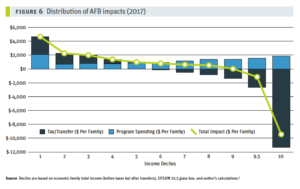

The Federal Reserve should not be raising rates. This is not the time. In both countries, what we need is fiscal stimulus and massive investments in public infrastructure. Unfortunately, ideological and political nearsightedness will prevent that from happening, virtually guaranteeing a prolonged period of misery.