This guest blog post has been written by Louis-Philippe Rochon.

You can follow him on Twitter @Lprochon

–

Harper’s recent incarnation as an anti-terrorist crusader has caught many Canadians by surprise. Harper is spending considerable political energy beating the drums of war against terrorists, and introducing a far-reaching, and much condemned, bill aimed at restricting free speech, and increasing police powers. But could this move hide a more cynical purpose? Can there be an ulterior motive?

I think there is, and the reason is quite simple. It’s the economy. Seven years after the beginning of the crisis, and 4 years after the official end of the crisis, the economy is slowly (or not so slowly) heading in the wrong direction. In fact, I don’t think we can exclude the possibility of a recession late in 2015 or early 2016.

Consider the economic facts. In 2014, the Canadian economy had a rather weak year. In November, the economy actually contracted by 0.2% mainly as a result of a weak manufacturing sector. It is the economy’s worst performance in almost a year: on a year-over-year basis, growth in Canada slowed to 1.9% from 2.3% in November.

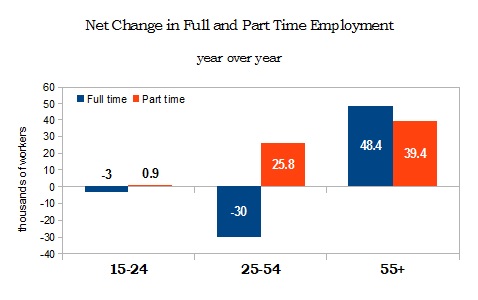

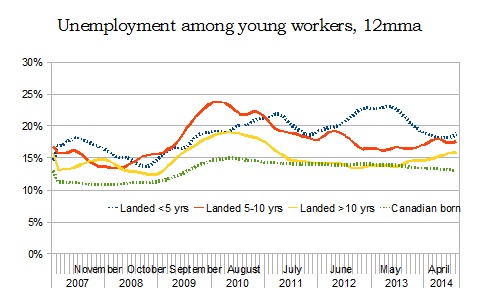

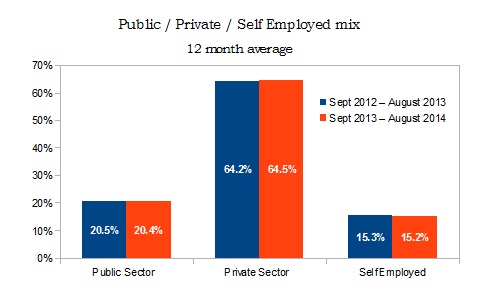

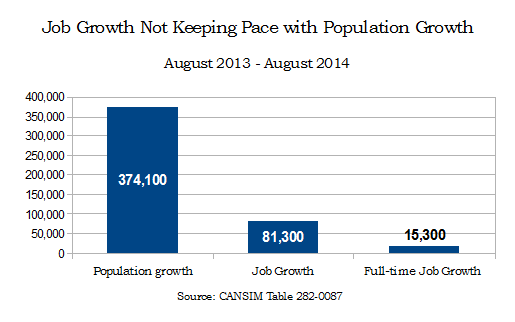

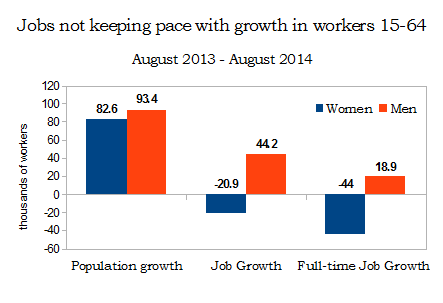

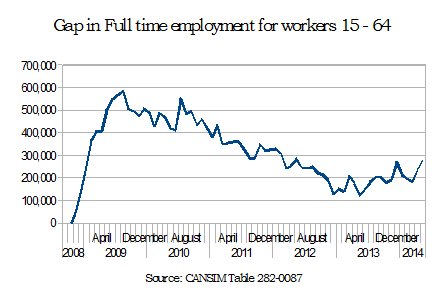

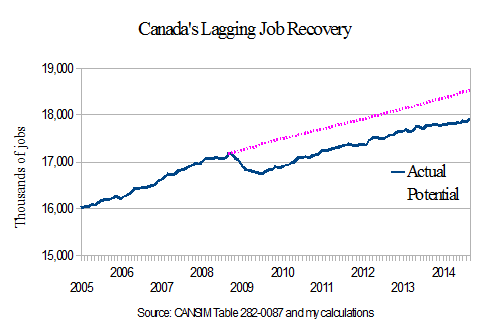

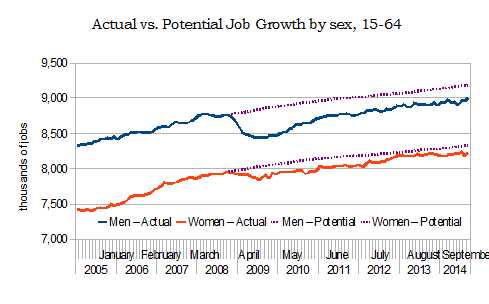

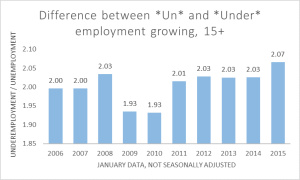

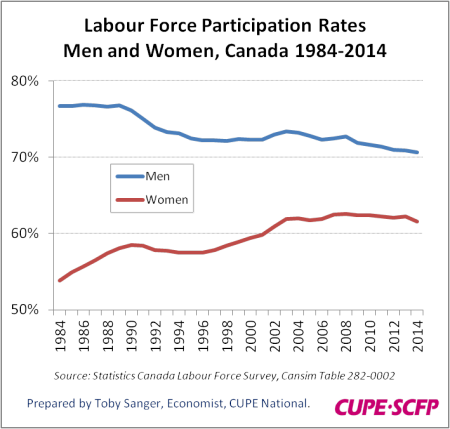

As for the labour market, unemployment is up, and job creation is down, and we are still nowhere near pre-crisis levels. In Statistics Canada’s labour market revisions last week, unemployment rate inched upward to 6.7%. Moreover, the Canadian economy in 2014 only created 121,300 jobs and not the 185,700 jobs initially reported. That’s an enormous discrepancy, a 35% discrepancy to be exact. On top of that, the economy actually shed jobs in the last 2 months. As for the labour force participation rate, it now stands 65.7% (revised down from 65.9%). Right before the crisis, it stood at roughly 67.7%. At this point in the recovery, we should be doing much better.

The recent decline of the loonie could be seen in some positive light, because it may lead to an increase in exports especially in vote rich Ontario and Quebec, but for this to occur, our trading partners’ economies must be growing at some respectful rates. And I am thinking here more of the US and China.

Everyone is predicting strong growth in the US economy in 2015, yet after growing at close to 5% in the 2nd and 3rd quarters of 2014, the US economy has slowed down to 2,6% in the 4th quarter (lower than expected); in fact the 2013 Q4 to 2014 Q4 growth rate was only 2.5%, which is less than the 3.1% recorded in 2013.  Now, just released, November’s US trade deficit is up, and there are expectations that December’s growth rate will come in below 2%.

In November, Canada’s manufacturing sector shrank by 1.9% even though our dollar was falling. This was a surprise to market observers who were expecting a slight upward bump.

And then, there is the question of our monetary policy. The Bank of Canada’s Hail Mary reduction in interest rates a few weeks ago (in an international beggar-thy-neighbour poliy, it seems) was a clear admission of the malaise creeping into the economy.

And now, the yield curve, a spectrum of yields on bonds of various maturities, has inverted. As of last week, the return on 5-year bonds fell below the overnight rate of 0.75. Now this is a big deal and it does not happen often. This is a sign that markets are factoring in another decrease in overnight rates, and reflects a general uneasiness about the direction in which the Canadian economy is going.

In fact, in some research of the US economy, it has been shown that a yield curve inversion more often than not announces a recession possibly as early as 6 to 9 months later. Yield curve inversions are usually followed by a credit crunch, where banks are more reluctant to lend, and the economy slows down. If this view holds, then we could possibly be looking at a recession in Canada anytime in between July and October – smack in the middle of a federal election campaign!

With his economic cards on the table, Harper’s hand is proving to be very weak. In order to win an election, he must create momentum, but the state of the economy won’t give him this opportunity. Note how silent the PM has been lately on the economy.

Armed with the same data, his advisers are surely telling him to avoid talking about the economy. So if you are the Prime Minister who has prided himself on strong economic policies, who has boasted his government’s record on prosperity, what can you do?

Well, the answer is simple: change the channel. In other words, redirect the debate toward something else, something that will hopefully distract the voters. But this issue must be big, something so terrible in fact that no one will even remember that the economy is heading in the wrong direction.

Enter the war on terrorism. Perfect topic. After all, who is not in favour of fighting terrorism? Harper will surely paint all those against him as terrorist sympathizers, and the opposition has fallen into the trap. And the timing could not be better: Parliament Hill in Ottawa just got attacked, and so were the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris. So let’s strike when the iron is hot.

Unfortunately, voters’ attention span is limited, and even the war on terrorism cannot be sustained for a whole 8 months. So expect Harper to do the next best thing: call an early election. This will serve two purposes: keep the terrorism debate alive for a much shorter time, but also avoid the unpleasant and inconvenient discussion of what is happening to the economy, and face the electorate when the economy gets too obvious that it can no longer be ignored.

It will be up to the Opposition parties to keep the economic topic alive, and Harper will try everything to avoid talking about it.